The Pectoral Cross of the 6th Bishop of Kurunagala

OBJECTIVE

To foster peace and harmony among various ethnic and religious groups through my academic, pastoral and administrative strengths, experiences and abilities to create a better future for the citizens of the world

Academic background

Doctor of Divinity(Hon DD)- Sociology of Religion with Theological implications and repercussions

17 May 2022

St Andrew's Theological University - India

Ethnographic research with a thesis on "Creation & Recreation of Identities"

Master of Philosophy (MPhil)-(Theology & Sociology of Religion) 2005, University of Kent, UK

Followed & completed the “Foundation Course for Part Time Youth and Community Workers” in Kent county Council. UK – 2002

Master of Philosophy (MPhil)-(Sociology with theological implications) 2001, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka

Bachelor of Divinity (BD) 1993, University of Serampore, India. (Theology Postgraduate study of three years)

Bachelor of Theology(BTh) 1989, University of Serampore, India

College Diploma (1985-1989) – Theological Education and Formation - Theological College of Lanka, Pilimatalawa, Sri Lanka

The Engineering Council , London. UK. Part I examination – May 1984 – Credited with passes in following subjects

(201) - Mathematics (203) - Properties of Materials - (208) - Thermodynamics

The story of the pectoral cross

ඉහලින් තල් ගසින් පෝෂණය උන

පහලින් පොල් ගස කප් රුකක් උන

මැද කඳුකරේ තේ වලින් සශ්රීක උන

මේ දිවයිනේ කොස් ගස බත් ගසක් උන

[ A free English translation :-

Fed by palm trees above

Below coconut trees are a treasure

Fertile tea in the central hills

The jackfruit is a rice tree in this island]

My books so far....

Ecclesiastical Experiences

Archdeacon of Nuwara Eliya - Diocese of Colombo

2016 - 2018

i. Vicar – St. Francis of Assisi, Mt. Lavinia

2015 – 2017

ii. Chair – Interfaith Desk of the Diocese of Colombo

2010 -2015

iii. Chaplain – St. John’s Home, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka ( A girl’s home and a children’s centre managed by the Sisters of St. Margaret (SSM) )

2011 – 2015

iv. Area Dean - Moratuwa and environs

2012 – 2015

v. Incumbent - Holy Emmanuel Church, Moratuwa with St. Paul’s ChurchMoratumulla, St. Michael and All Angel’s Church, Willorawatte, Church of the Healing Christ, Kadalana, and Anglican Church at Uyana.

2011 -2015

( < www.holyemmanuelchurch.com=""> )

vi. Examining Chaplain – Diocese of Colombo – to date

vii. Member – “ Priests” clergy choir of the Diocese of Colombo - Through this choir of 6 clergypersons we have been promoting Gospel values. My interest in music and singing has promoted discipleship among various people – to date

viii. Pastoral experience in the parish of Christ Church, Mutwal ( former Cathedral of the Diocese of Colombo) and missions

2010 March to 2011 Jan

ix. Have experience of pastoral ministry in the following parishes/institutions in Sri Lanka

1. Ratmeewala 2. Wattegama 3.Gampola 4.Gatamge 5. Peradeniya training colony Chapel 6. University of Peradeniya Chapel

1996 Jan – 2010 March

x. Sri Lankan representative of the NIFCON (Network for Inter Faith Concerns)

2006 to date

xi. Licence to officiate in the Diocese of Kurunagala, Sri Lanka

1996 – 2010

xii. Director – Fulltime Lay workers of the Diocese of Colombo

2006-2009

xiii. Licence to officiate in the Diocese of Canterbury. UK. (PTO)

2002 – 2007

xiv. Worked for the Whitstable Team Ministry in the Diocese of Canterbury.UK

2001 – 2005

xv. Anglican minister in the Diocese of Colombo

1989 – to date

xvi Member, Ministerial Advisory Committee, Diocese of Colombo

1996- 2001 & 2005 – 2010

xvii. Chaplain, Denipitiya Medical Mission, Sri Lanka.

1993-1996

xviii. Chaplain, Hillwood College, Kandy, Sri Lanka.( An Anglican College started by CMS missionaries in 1890 )

1999- 2001

xix. Youth Chaplain, Southern Deanery of Sri Lanka.

1993- 1996

xx. Vicar, Church of the Ascension, Matara, Sri Lanka.

1993-1996

xxi. Assistant Curate, All Saints Church, Galle, Sri Lanka.

1992

xxii. Assistant Curate, St. Marks Church, Badulla, Sri Lanka.

1989-1991

~ The cross of the Diocese of Kurunagala is a replica of the 6th century Nestorian cross unearthed from the ancient Kingdom of Anuradhapura in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka ~

● Top part of the Cross – Palmyra palm wood from the North of Sri Lanka # Bottom part of the cross – coconut wood from the South of Sri Lanka# Middle part – Tea wood from the central hills of Sri Lanka # Bottom base – Jak wood grown in all parts of Sri Lanka●

< the="" self-giving="" love="" of="" the="" cross="" embraces="" all="" cultures="" of="" sri="" lanka="">

E mail frkeerthi@gmail.com - Personal

Content......

1. Insufficiency of mere "dialogue" for the 21st century

2. Religious conversion - A reflection

3. Ethno-religious identities in the global village

4. “English” in Sri Lanka

5. Minority Christian Identity in the Context of Majority Buddhist Identity in Sri Lanka

6. WISDOM STORIES FROM RELIGIONS

7. INTERFAITH DIALOGUE – AN APPRAISAL

8. Sinhala Buddhists and Christians

9. The future of Tamil people in Sri Lanka - 2009

10. Call for Moral Passover from Babel to Pentecost

11. “Xenophilia”

12. Significance and Derivation of Christmas

INTERFAITH DIALOGUE – AN APPRAISAL

As the concept called interfaith dialogue has been around for well over half a century it is high time to evaluate the effect of this notion in society. It is not a coincidence that this concept came into being as a post colonial and post Second World War reality in the context of the loss of the Western colonial power in Asian countries such as India and Sri Lanka.

A closer look at interfaith dialogue reveals that it was mainly the Westernised English speaking middle class elite of the Christian church who initiated this process. This group was ethnically composed of Sinhala, Tamil and Eurasian people along with some Europeans. This shows that for these people interfaith dialogue was a binding factor irrespective of their ethnic affiliations. One may assume that they came together for this process because of their common faith of Christianity. However to have a sound coherent understanding of this issue it is necessary to look into other factors that made them interested to commence this process called interfaith dialogue.

It is not a secret that this category called the Westernised English speaking middle class elite of the Christian Church was well established, having social and political power under British colonial rule. Under the British this power was cemented by their Christianity (especially the Anglican branch of the Christian Church). However, when colonial rule ended they lost this prime position that they had had through their faith. Not only this particular elite of the Christian church in Sri Lanka and Asia but also the Western colonial powers had to comprehend the bitter reality that Christianity was more of a hindrance rather than an assistance to keep some grip on their former colonies. Here the possible effective and evident alternative was “interfaith” rather than “Christianity.” In this process it is very intriguing to note that what they inaugurated with “interfaith” was not a “relationship” but a “dialogue.”

After more than five decades it is very apparent that the positive effect of this process is very minimal among the common people in the pews of the Christian church. Instead we can observe a very negative resistance to this dialogue by many Christians in Sri Lanka. Here it is necessary to look into this phenomenon to evaluate the effect of this concept in society.

This process took ethnicity and other grass root realities such as poverty and identity created through religion into minimum consideration. Therefore for ordinary Christians this process did not become very meaningful as a living experience. Also many ordinary Christians were frightened by what is called “syncretism,” where they believed that Christian faith would be watered down through this process called interfaith dialogue. For this reason the response especially of Charismatic and evangelical Christians to interfaith dialogue has been very pessimistic and negative.

However the fact cannot be ignored that to live in harmony we have to live together as sisters and brothers irrespective of our various identities (religious, ethnic, cultural, etc.) which are decisive in creating meaningful boundaries to feel secure in society. But the aforementioned analysis reveals that the process called interfaith dialogue has not been meaningful or powerful enough to promote and instigate this effective harmonious living in our society.

In this context what is necessary is to fashion a situation where people could reduce xenophobia, which is fear of the encounter of strangers, “foreigners” and unknown phenomena faced by various groups in society. To responded to this situation it can be proposed that it is appropriate to introduce a progression which could be called “ xenophilia” where people are encouraged to formulate positive healthy relationships with so-called strangers, “foreigners” and unknown phenomena by crossing one’s own boundary. This process could create space for each community to wrestle with its own issues rather than handling their concerns in a structure created by somebody else to meet their own ends.

2.

Religious conversions

A reflection

Religious conversion is a controversial issue often debated in Sri Lanka. Apart from inflammatory writing and argument there have been cases of physical assault, maybe with the intention of preventing a conversion. I believe we first need a proper understanding of why anyone should seek to change from one religion to another - if not from a genuine spiritual conviction. A common allegation, if not the only one, is that many have been converted for the sake of money and material wealth. (I have met people who come into this category.) Why would anyone change their faith for a material motive? When people in real material need get support from individuals or groups they may feel it is good to identify themselves with those who are willing to support them. This is a natural human response, and I believe every human being has the right to do this. Yet I also strongly believe it is the responsibility of people who help the needy not to encourage them to change their religion just for money or material things.

Can we really call such a change a 'religious' conversion? I have doubts about this from experience of living in Sri Lanka. Some who are of this mind and purpose keep moving from place to place to get support here and there and so overcome their material difficulties. However, as they don’t remain in one place for long there's hardy anything 'religious' in their conversion. Some others who have been given material support identify with those who helped them - for a time - but when they realise they can get no more help they gradually dissociate themselves from those who supported them. It's clear that people who try to change their religious identity for material needs often fail to keep their new faith when they cease to get help.

Does this imply that there are no true religious conversions? Not at all. But if we want a proper understanding of these conversions, first we should understand the reality of change. It is a fact that whether we like it or not we all keep on changing. This is well explained in the Buddhist concepts of Dukkha, Anicca and Anatta. Some people change their identities due to various social reasons within their community. When people are not accepted and respected in a community they seek to change their identity. They may change religions to gain more acceptance and respect and to feel comfortable within the community. Others who face a crisis such as sickness change their beliefs to get blessings and healing and overcome the problem they are faced with. Some others aim to change their social class by changing their religion and settling in the new class they have chosen. Many other reasons can be given for religious conversions within a society.

In Sri Lanka in particular there is a need for a practical solution to overcome the tension between various religions. Here I would like to suggest a method that I adopted in various parts of the country - to handle religious conversions in consultation with religious leaders of the community. When someone expresses a wish to change their religion they could be counselled by a leader of the faith they presently belong to and also a leader of the faith they wish to embrace. This kind of understanding is specially important in areas which are, in the main, traditionally of one faith.

I believe that if this strategy could be adopted in Sri Lanka it would help to strengthen understanding between different religions when faced with the issues of religious conversions.

3.

Ethno-religious identities in the global village

In this 21st century people all over the world have become aware of how far away places are being brought closer together into a so-called ‘global village’. This trend is enhanced by modern communication and transport systems such as the Internet, e-mail. high- speed trains and planes. The phenomenon of the global village makes it necessary to understand how local adaptation is often coloured by ancient ethno-religious identities. . Today people of various ethnic and religious groups live closer to each other than in past centuries and there is a general expectation that they will gradually forget their identities within the melting pot of the global village. Often this expectation is fuelled by countries who are stand most to benefit from globalism.

It is natural for countries and communities who are potential losers in the global movement to seek ways of regaining the lost power and prestige that globalism brings. With the threat of losing so much they have only their ethnic and religious identities as a basis for coming together to regain what they have lost. The question may be asked as to why they focus on ethno-religious identities rather than political systems which could help them fight to regain what they have lost in the global economy. But political systems often have to go along with global tendencies for their survival and people are reluctant to resist or work to prevent policies implemented by the most powerful countries of the world.

Many so-called Third World countries have been reviving their ethno-religious identities politically - at times with extreme tendencies - as a response to global tendencies. Often they have taken an anti-western stance in response to the centralisation of global powers in the west. These ethno-religious identities are becoming further strengthened as a result of the western standardisation of such aspects of human life as materialism, cultures and political systems where some minorities are even faced with actual extinction.

Nor can we overlook the way in which ethno-religious identities were used by nations in the 20th century to gain independence from western colonial rule. The fresh memories of these struggles for independence have encouraged peoples in Third World countries to use their ethno-religious identities once again to fight the forces, which threaten their very existence in the world.

Is it not, therefore, the responsibility of the western world to be sensitive to the ethno- religious identities of poorer nations and to avoid the extreme steps taken by some groups in those countries? Otherwise it will be difficult to prevent the expansion of groups, which threaten peace throughout the world. If the current tendency of rich countries to become richer while poor countries become poorer is not checked it will be hard to stop people in poorer countries taking extreme steps - feeling they have nothing to lose.

4.

“English” in Sri Lanka

The word “ English” could mean many things to people in Sri Lanka. Whatever the meaning the very word “ English” frightens many Sinhala and Tamil educated people who have little knowledge of English culture and language. The environment created by the English educated elite mainly causes this Anglophobia in Sri Lanka.

Today some influential English educated people in Sri Lanka live in a fantasy world and try to emphasis the “Oxford” or “BBC” English as the correct and accurate English, which should be used in Sri Lanka. In a way these people are trying to keep colonial Victorian English alive with an emotional attachment to this type of the language which made them, or their relations, masters of other Sri Lankans under colonial rule. What they have not realised is the fact that today, even in the “Oxford” or “BBC” type language culture in the UK, it is hard to show an homogeneous type of the English language or pronunciation as, for example: the BBC particularly tries now to function as an area in which people with a wider variety of regional accents and with language structures from all over the world are included. Not only in these areas but also in many parts of the world, with the influence of globalisation, people are using English in a multiplicity of ways for communication.

The culture that these English educated elites have created in emphasising so called “ Oxford” or “BBC” English” has been humiliating many Sinhala and Tamil educated people, giving the impressing that they are “fools” or “uneducated” in Sri Lanka. Often these English educated elites suffer from “ teacher mentality” and keep on correcting the little English used by Sinhala and Tamil educated people to show their authority over them. It is the responsibility of Sinhala and Tamil educated people to take measures to prevent this teacher mentality to allow the majority of the population to learn English without undue pressures in the society. Sinhala and Tamil educated people should not be misled by these elites as they come from the same tradition as the people who stressed -after independence (specially after 1956) - that Sinhala and Tamil are enough for Sri Lankans.

In a country like Sri Lanka it is useful to stress English in two different ways. First of all it is the link language that is used to bring together various ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. Secondly English is the best international language to enable all Sri Lankans to widen their horizons in order to gain exposure to the rest of the world. The best example for this type of usage of English is found in our only immediate neighbour and big sister India.

In this situation it is high time for Sri Lankans to promote English for communication with basic grammar and a clear understandable accent and to eradicate the elite approach of keeping English as a way of life for their superiority survival.

5.

Minority Christian Identity in the Context of Majority Buddhist Identity in Sri Lanka

Introduction, Scope of Study and Method

In this short paper it is expected to examine the identity issues of Christian minority in the surroundings of Buddhist majority in Sri Lanka. This is done by considering sociological realities connected to Buddhist and Christian identity with theological inputs that have been necessarily associated with the identities of these world religions. Hence this paper highlights theological issues as long as they are empirically intertwined with the identity concerns of the people of these two scripture-based religions in Sri Lanka.

Although this study mainly discusses the issue of Christians in the context of Sinhala Buddhism, to enhance the scope of this research other realities such as Tamil ethnic presence are taken into consideration appropriately. Through scrutiny an effort is made to investigate the possibilities of contributing to ethno-religious harmony in Sri Lanka by understanding the identity of Christians in the bosom of Buddhism. Yet it is not the intention of this paper to have an extensive analysis of the Buddhist and Christian communities and post-war situation in Sri Lanka.

This brief research is done by placing Sri Lankan context in the global realities and research appropriately. The substance of this paper is obtained from the written literature and the living experience of the writer of this research. Other necessary information and views have been accessed from the writer’s previous research of similar vein in Sri Lanka and the UK.

A very brief introduction to the social history of the Christian community in Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka Buddhism is the majority religion (69%) and Christianity is one of the minority religions (7.6%) of the people of this land. Although almost all the native Buddhists in Sri Lanka are Sinhala people the reverse is not the case. About 4% out of the 7.6% Christian minority are Sinhala. Approximately 3.6% are of Tamil ethnic origin. [1]

The continuous existence of the present day Christian community in Sri Lanka can be traced to the arrival of the Portuguese at the beginning of the 16th century. This was followed by the Dutch in 1658 CE and then the British in the year 1796 CE. The Portuguese introduced Roman Catholicism while the Dutch established the Dutch Reformed Church, and under the British colonial rule many so-called Protestant denominations such as Methodist and Baptist were initiated along with the religion of the colony called the Anglican denomination.

Although all these colonial powers protected and used their brands of Christian denominations for their own benefit to run the colony, there are some unique features which need to be recognised to create the background for the present research. The Portuguese were involved in mass conversion and used many visual aids and symbols in proclaiming Roman Catholicism. Their priests were celibates and did not depend on the salary from the colonial government. They led a simple life and got involved with the common people in their everyday activities. The Dutch introduced the Dutch Reformed Church by prohibiting all the other religions including Roman Catholicism. They were particularly against Roman Catholicism as the Dutch belonged to the reformed camp who were against the Roman Catholics whose head was the Bishop of Rome (the Pope). Under these circumstances the Portuguese persecuted the Roman Catholics, which created pandemonium among the Roman Catholics in Sri Lanka. The British allowed the flow of many denominations and gave religious freedom to all religions, although special privileges were granted to the Anglican Church. [2]

In 1948, after political independence, Christians lost the many privileged positions that they enjoyed under the colonial regime. Under these circumstances some Christian denominations initiated processes such as indigenisation and inculturation to face the challenges of the postcolonial era. Generally until the mid 1970s the foreign contacts of the Christians were very much restricted. After that time, with the introduction of the market economy in the context of so-called globalisation, once again Christians were able to have a close connection with their foreign counterparts. In this background many new Christian denominations have been introduced to Sri Lanka.

The Problem

The main problem unearthed by this research paper is identified as the tension between universality and particularity of two major religions existing in an island nation called Sri Lanka at the southern tip of India. To understand this problem the following explanation presented by Gunasekara, explaining the characteristics of a universal religion, can be considered useful.

Universality of Principle. There must be nothing in the basic beliefs of the religion that confine it to a particular nation, race or ethnic group. Thus if there is a notion of a "chosen people" then this characteristic is violated.

Non-Exclusiveness of Membership. Any person could be an adherent of the religion concerned, and be entitled to the same privileges and obligations as every other person. This of course does not require every follower of the religion to be of the same level of achievement, but only that some external factor like race or caste prevents individuals from full participation in the religion.

Wide Geographical dispersion. The religion must have demonstrated an ability to find followers amongst a variety of nations or ethnic groups. Thus even if a religion satisfies the first two requirements but has not been able to spread beyond its region of origin it may not qualify to be a universal religion. Thus Jainism is not generally regarded as a universal although its principles are universal in scope and it is non-exclusive.

Non-Exclusiveness of Language. The practices of the religion which require verbal communication should be capable of being done in any language. The authoritative version of its basic texts may be maintained in the original language in which the original expositions were given, but translations of these should be valid, provided that they preserve the sense of the original texts.

Independence of Specific Cultural Practices. The practices of the religion should be free from the cultural practices of a particular group in such matters as food, dress, seating, etc.

Each one of these criteria raise problems but they have to be satisfied to a significant extent if the religion is to be deemed a universal one.[3]

Although in Sri Lanka these two religions, Christianity and Buddhism, basically endeavour to abide by these factors, in creating the identities of the adherents they have the tendency to shift from these features. Dynamics of this inclination create a variety of issues integrally connected to the identities of these religious categories. Hence through this paper it is expected to elaborate this phenomenon to contribute to the area of this research.

Basic Theoretical Framework

The nexus between ethnicity and religion is the foundation of the theoretical framework of this paper. This is done by taking precedence from the theory created by Yang and Ebaugh from their extensive research done on this subject. According to these two scholars the nexus between ethnicity and religion can be identified in three main categories. They are the “ethnic fusion” in which religion is considered as the foundation of ethnicity, “ethnic religion” where religion is one of the many foundations of ethnicity, and thirdly “religious ethnicity” in which case an ethnic group is associated with a particular religion shared by other ethnic groups. [4] This framework in enriched by the theory presented by Hans Mol and others on boundary maintenance and change handling of the religious groups. [5] This is done to examine the creation and recreation of Christian identity in the context of dynamic Buddhist identity in Sri Lanka.

An Analysis

In a country like Sri Lanka, where beliefs and philosophies are taken seriously, in all endeavours, these aspects play a vital role in determining behaviour patterns of people in society. In this background it is indisputable that these features have been an integral part of the happenings in Sri Lanka. Hence folk beliefs and organised religious beliefs amalgamated with ethnicities have become the key factors in both fuelling tension and also showing the capacity to reduce tension to have a better understanding of each other in society.

Up to the present day Buddhism has existed for almost 22 centuries in Sri Lanka. Along with Buddhism, rituals, ceremonies and practices connected to Hindu religiosity have been surviving in this island land. As Middle Eastern and South Indian traders have been visiting Sri Lanka for a very long time, with the rise of Islam in the seventh century, gradually Islam also was established in Sri Lanka.

Beginning from the 16th century with the introduction of Christianity under the colonial regime, the well-established Buddhist identity has been undergoing drastic changes in Sri Lanka. To face the challenges posed by the colonial powers Buddhists have progressively been strengthening their identity on ethno-religious lines. This process, which began as a colonial reality, has been developing in many directions to recreate the denied honour of the Sinhala Buddhist under colonial rule.

Sociologically speaking, Buddhist revivalists came to have a “love-hate” relationship with the Christians, which became prominent after mid 19th century. Bond has explained this in the following manner.

Protestant Buddhism the response of the early reformers who began the revival by both reacting against and imitating Christianity……….[6]

In this process Buddhist revivalists started establishments such as schools and organisations by adopting and adjusting the structures of the Protestant church. Buddhist worship, rituals and ceremonies went through drastic changes. For instance, Buddhists revivalists started Buddhist carols or Bhakthi Gee by adapting the form of Christian carols.

On the other hand, after political independence in 1948 CE, Christians have been trying to become effective by adopting, adjusting and adapting many phenomena from the Buddhist philosophy and culture in Sri Lanka. These are aspects such as church architecture, music and cultural symbols from the traditional Buddhist context in this country.

After political independence in 1948 CE, slowly but steadily the majority Buddhists have been strengthening their identity with the Sinhala ethnicity. Over the years the consciousness of Buddhists as the chosen people of the soil and of Buddhism as the foundation of their Sinhala ethnicity have been increasing, creating many decisive issues in Sri Lanka. This has contributed towards the creation of an identity crisis for Sinhala Christians who do not share the same philosophy, although they share many cultural elements with Sinhala Buddhists in Sri Lanka.

The encounter of Buddhism and Christianity over five centuries have been a theologising experience for both these religions in Sri Lanka. However, the very word “theology” in Christianity has raised many issues for Buddhists who believe in a religion where God or gods are not at the centre of their faith. Regarding this Smart has noted,

The thought that you could have a religion which did not in any straight sense believe in God was a novel thought in the West and still has hardly been digested.[7]

Sinhala Buddhists in Sri Lanka have been strengthening this position to claim that the saving power according to Buddhism is within human beings without necessarily getting assistance from any supernatural entity. [8] Davies has explained this in the following manner,

deepest kind of mystical experience and quest can exist independently of theism…[9]

This belief at times directly and indirectly has been used to counteract Christianity in which theologically God is the centre of all realities. Consequently Buddhists have been working hard to achieve their goals with human efforts, often reminding themselves of a famous saying of the Lord Buddha: “One’s own hand is the shade to his own head.”

.Although it is not required to believe in God or gods to be a Buddhist, the pantheon of gods has a very significant place in popular Buddhist worship. However in Buddhist belief these gods are “much lower than the Lord Buddha.” [10] At the same time, according to Buddhist belief these gods are lower than human beings as well.

Yet the interaction of ordinary Buddhists in certain Christian worship activities is a visible reality in Sri Lanka. In this regard it is highlighted by some scholars that anthropologists have misapprehended the certain behaviours of ordinary Buddhists. The following observation by Gunasinghe highlights this reality,

A Buddhist Sinhalese who takes a vow at a Catholic church will not imagine that he is taking a Buddhist vow, for there are no such vows in Buddhist practice. A Buddhist who wishes to benefit from the laying on of hands by a Catholic priest does not look upon the ritual as a Buddhist act. The distinction that a Buddhist makes in such situations is not a matter of form: it is a matter of fundamentals. Anthropologists seem to deal often only with form and not fundamentals, and to that extent their findings call for caution. [11]

Not only anthropologists but also some Christians have not been grasping this issue of form and fundamental of the conduct of these Buddhists in Sri Lanka. Although in the purview of this study it is not possible to elaborate this matter, for better understanding between Buddhists and Christians this needs to be studied carefully.

In the recent past Buddhists have been accusing Christians, saying that they convert Buddhists through unethical means. In this regards, apart from inflammatory writings, there have even been physical assaults on Christian churches. Efforts have even been made to bring legislation to prevent this so-called unethical conversion. Although in a short paper of this nature it is not possible to elaborate all the issues related to this reality, let us highlight some important concerns.

First of all the fact should be taken into consideration that today the Christian minority as a community does not enjoy significant political or military power in Sri Lanka. Then the question is why some Buddhists are threatened by some of their activities? Today the Christian minority is about 7% and is geographically well spread in Sri Lanka. They use all three main languages of Sri Lanka (Sinhala, Tamil and English) equally in their activities. Ethnically Christians are comprised almost equally of Sinhala and Tamil, the two main ethnic groups of Sri Lanka. Among Christians the literacy rate is almost 100% and the knowledge of English, the international language, is higher than in the other groups in Sri Lanka. The percentage of international relationships of Christians is also better than the other groups in Sri Lanka. These realities clearly show that Christians have a disproportionate representation in Sri Lanka. In other words it can be said that the Christian minority has been living with a majority psychology owing to these facts.

On the other hand Buddhists mainly confine themselves to the Sinhala language for their activities, and almost all the Buddhists ethnically belong to the Sinhala category. Unlike Christians, the majority of the Buddhists in Sri Lanka live in rural areas where they are not much exposed to international realties in the world. These circumstances have caused these Buddhists to develop a minority psychology in this country.

The tension between Sinhala and Tamil ethnic groups has been making Sinhala Christians vulnerable in the area of boundary maintenance for the identity making of this group. These Sinhala Christians were often forced to have a dichotomy in their identity in Sri Lanka. In this dichotomy this Sinhala Christian group has been identifying religion-wise with Tamil Christians while ethnically they were doing the same with Sinhala Buddhists. Therefore this state of affairs has created an identity crisis for the Sinhala Christians in the bosom of the Sinhala Buddhist majority in Sri Lanka.

Conclusion

The brief analysis shows that Christians and Buddhists have been living with a kind of xenophobia in Sri Lankan society. Christians have been expanding their boundaries with the international realties, perhaps with little attention to the contextual realties around them. On the other hand Sinhala Buddhists have been strengthening their local identity with Sinhala ethnic group that have developed phobias for many groups including Christians. This shows the necessity of keeping both global and local realities in proper balance and tension by both Buddhists and Christians in Sri Lanka.

Hence it is clear that the mutual enriching and enhancing of these two world religions both sociologically and theologically could inspire “xenophilia” instead of the prevailing xenophobia in Sri Lankan society.

[1] Somaratna, G. P. V.(1992), Sri Lankan Church History (In Sinhala) , Marga Sahodaratvaya, Nugegoda. Sri Lanka.

[2] Somaratna, G. P. V.(1992), Sri Lankan Church History (In Sinhala) , Marga Sahodaratvaya, Nugegoda. Sri Lanka.

[3] Gunasekara V.A.(1994), An Examination of the Institutional Forms of Buddhism in the West with Special Reference to Ethnic and Meditational Buddhism, The Buddhist Society of Queensland, PO Box 536, Toowong Qld 4066, Australia. <>http://www.buddhanet.net/bsq14.htm >

[4] Yang, F. & Ebaugh, H.E. ( 2001), ‘Religion and Ethnicity Among New Immigrants :The Impact of Majority/ Minority Status in Home and Host Countries’, Journal for Scientific Study of Religion, 40:3 p.369.

[5] Mol, Hans (Ed)(1978), Identity and Religion: International, Cross Cultural Approaches, Saga Publication Ltd, 28 Banner Street, London. p.2.

[6] Bond, G. D. (1988), The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka, , Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, p.5.

[7] Smart, N. (1984), ‘The Contribution of Buddhism to the Philosophy of Religion’, in ‘Buddhist Contribution to World Culture and Peace’, Edited by N.A. Jayawickrama, Mahendra Senanayake, Sridevi Printing Works, 27, Pepiliyana Road, Nedimala – Dehiwala, Sri Lanka, p. 89.

[8] Davies, D.J. (1984), Meaning and Salvation in Religious Studies, E.J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands. P.1.

[9] Smart, N. (1984), ‘The Contribution of Buddhism to the Philosophy of Religion’, in Buddhist Contribution to World Culture and Peace, Edited by N.A. Jayawickrama, Mahendra Senanayake, Sridevi Printing Works, 27, Pepiliyana Road, Nedimala – Dehiwala, Sri Lanka, p. 90.

[10] de Silva, L.(1980), Buddhism : Beliefs and Practices in Sri Lanka, Ecumenical Institute, 490/5, Havelock Road, Colombo 6, Sri Lanka , p.63.

[11] Gunasinghe, S. (1984), ‘Buddhism and Sinhala Rituals’, in Buddhist Contribution to World Culture and Peace, Edited by N.A. Jayawickrama, Mahendra Senanayake, Sridevi Printing Works, 27, Pepiliyana Road, Nedimala – Dehiwala, Sri Lanka, p.38.

6

WISDOM STORIES FROM RELIGIONS

HINDU

Once upon a time there was a wise merchant who had five sons. One day he asked each son to find a stick . When they each had one, their father told them to break the sticks which they did without any difficulty. Then the father colleted the broken sticks and bundled them up together to teach his sons a lesson.

Father then handed the bundle to each of the sons asking them to break it. But it was so strong no one was able to break it.

Then their father said, “ If you are bound together you are very strong”

BUDDHIST

(Elephants at Kandy Perahara , Sri Lanka)

This story was told by Buddha to show how the problems between religions are something like the Blind men and the Elephant.

Once upon a time there was a king who asked his servant to call all the blind men in the town to a certain place in that town. He then presented the blind men with a large elephant and asked each man to touch the elephant: one to touch the ear, another the tusk, another the trunk and so on. He then asked each blind man to describe the elephant. The one who touched the tusk said it was like a plough, the one who touched the tail said it was a brush, the one who touched the leg said it was a pillar. As the blind men began to disagree with each other’s views they became very cross and started hitting each other.

ISLAM

In the Quran (80.24) Allah said: “Then let man look at his food.”

You live in England and your mother prepares fish for you to eat. This fish may have come from Sri Lanka. Allah tells his followers to look at their food to see where it came from, how it came, how it was created, etc. Allah created this particular fish in a river in Sri Lanka. Then Allah gave it food and looked after it so that it grew up. Allah then caused a fisherman to catch the fish and sell it to another person. Then Allah caused that person to send the fish all the way to England where someone bought it from a stall. Then the fish was cooked and served on your table. Allah did all these things so that you could have something to eat!

CHRISTIANITY

A parable narrated by Jesus

Once a certain father had 2 sons. One day the younger son asked his father to give him his share from his father’s wealth. The father divided his wealth and gave the younger son his share. This young man took his wealth and went to a faraway country where he spent it all. Then there was a famine in the country and he had nothing to eat. In this situation he managed to get a job looking after pigs. While looking after them, as he was hungry, he ate the food their food . In this sad situation he remembered how even his father’s servants ate much better than this. Then he got up and decided to go back to his father and tell him how he had sinned against God and his father and was not worthy to be called his son. Therefore he asked his father to accept him back as one of his servants.

As he approached home he saw his father waiting for him and when his father saw him coming he was delighted and arranged a feast for him. As the feast was going on the elder brother came home after work and when he learnt that his younger brother had returned he was angry. He asked his father “ Why did you accept this your son who wasted your wealth”. Father said “ He was lost and found, therefore we should rejoice” But the elder brother was unhappy, saying that he had been there with him throughout his life but had not even received a small goat to enjoy with his friends. Then the father told him “all that I have is yours - please come and rejoice”.

7.

INTERFAITH DIALOGUE – AN APPRAISAL

As the concept called interfaith dialogue has been around for well over half a century it is high time to evaluate the effect of this notion in society. It is not a coincidence that this concept came into being as a post colonial and post Second World War reality in the context of the loss of the Western colonial power in Asian countries such as India and Sri Lanka.

A closer look at interfaith dialogue reveals that it was mainly the Westernised English speaking middle class elite of the Christian church who initiated this process. This group was ethnically composed of Sinhala, Tamil and Eurasian people along with some Europeans. This shows that for these people interfaith dialogue was a binding factor irrespective of their ethnic affiliations. One may assume that they came together for this process because of their common faith of Christianity. However to have a sound coherent understanding of this issue it is necessary to look into other factors that made them interested to commence this process called interfaith dialogue.

It is not a secret that this category called the Westernised English speaking middle class elite of the Christian Church was well established, having social and political power under British colonial rule. Under the British this power was cemented by their Christianity (especially the Anglican branch of the Christian Church). However, when colonial rule ended they lost this prime position that they had had through their faith. Not only this particular elite of the Christian church in Sri Lanka and Asia but also the Western colonial powers had to comprehend the bitter reality that Christianity was more of a hindrance rather than an assistance to keep some grip on their former colonies. Here the possible effective and evident alternative was “interfaith” rather than “Christianity.” In this process it is very intriguing to note that what they inaugurated with “interfaith” was not a “relationship” but a “dialogue.”

After more than five decades it is very apparent that the positive effect of this process is very minimal among the common people in the pews of the Christian church. Instead we can observe a very negative resistance to this dialogue by many Christians in Sri Lanka. Here it is necessary to look into this phenomenon to evaluate the effect of this concept in society.

This process took ethnicity and other grass root realities such as poverty and identity created through religion into minimum consideration. Therefore for ordinary Christians this process did not become very meaningful as a living experience. Also many ordinary Christians were frightened by what is called “syncretism,” where they believed that Christian faith would be watered down through this process called interfaith dialogue. For this reason the response especially of Charismatic and evangelical Christians to interfaith dialogue has been very pessimistic and negative.

However the fact cannot be ignored that to live in harmony we have to live together as sisters and brothers irrespective of our various identities (religious, ethnic, cultural, etc.) which are decisive in creating meaningful boundaries to feel secure in society. But the aforementioned analysis reveals that the process called interfaith dialogue has not been meaningful or powerful enough to promote and instigate this effective harmonious living in our society.

In this context what is necessary is to fashion a situation where people could reduce xenophobia, which is fear of the encounter of strangers, “foreigners” and unknown phenomena faced by various groups in society. To responded to this situation it can be proposed that it is appropriate to introduce a progression which could be called “ xenophilia” where people are encouraged to formulate positive healthy relationships with so-called strangers, “foreigners” and unknown phenomena by crossing one’s own boundary. This process could create space for each community to wrestle with its own issues rather than handling their concerns in a structure created by somebody else to meet their own ends.

8.

Sinhala Buddhists and Christians

In Sri Lanka there are 72% of Sinhala people who speak Sinhala language and live in the predominant “Sinhala” culture. Among them about 69% profess Buddhism as their religion while others belonged to Christian faith. In the recent past, due to many reasons, there were many incidents in Sri Lanka where there were tensions between Sinhala Christians and Buddhists.

There are some Buddhists who think that Christians are henchmen of past colonial era and consider them as enemies. Some others consider them as betrayers of Sinhala ethnic group. Perhaps another important contributory phenomenon for this is the fact that Sinhala Christians share their ethnicity with Sinhala Buddhists while having their common religion with Tamil Christians. Over and above all these, the main reason for tension is related to so call unethical conversions from Buddhism to Christianity. In this present situation, how can these two religious groups, who belonged to same Sinhala ethnic group could live in with peace and harmony?

Sinhala Christians should realise that although they profess Christian faith they belonged to Sri Lankan Sinhala culture and that it is also their duty to protect and preserver this unique culture. In this context it is their responsibility to search for a common Sri Lanka Christian identity not on western values but on the gospel proclaimed by Jesus Christ. As Sinhala people it is necessary for them to have a sound understanding of Buddhism, which has contributed immensely to the development of Sinhala culture in Sri Lanka. It is important for Sinhala Christians to learn that Sinhala Christians have not got rooted in Sinhala agricultural areas where the majority of Sinhala Buddhists live.

On the other hand it is important for Sinhala Buddhists to realise that Sinhala Christians are an integral part of Sinhala ethnic group although they profess a different faith. The majority of the Christians are part and parcel of Sri Lankan society and that they are proud of their Sinhala identity. It is helpful for Sinhala Buddhists to be aware that Sinhala Christians have created a predominant Sinhala fisher culture and a sub culture in the urban areas in Sri Lanka.

In the context of the development of religious “fundamentalism” both Sinhala Christians and Buddhists should take care not to come to conclusion that “My” faith is the only true faith and therefore “I” should despise all the other faiths. It is a visible reality of the growth of these groups in both Christianity and Buddhism who use arrogant methods to condemn other religions. It is the responsibility of Sinhala people whether Christian or Buddhists to take every possible step to avoid these extreme, unhealthy positions often promoted by tiny minorities.

As universal religions, Buddhism and Christianity have been able to get rooted in many cultures and societies. Therefore it is useful for Sinhala Christians and Buddhists to learn from other Buddhists and Christians of others cultures and societies where they live in peace and harmony respecting and helping each other.

9.

The future of Tamil people in Sri Lanka

2009

The Sri Lankan Government claims that they have wiped out the LTTEers from Sri Lanka. According to Government sources all the geographical areas are now under the control of the Sri Lankan Government. Announcing this “victory” the President of Sri Lanka said that now in Sri Lanka there are no “minorities” but only two sections of the society. They are the people “who love the Motherland” and those “who don’t love the Motherland”. In this whole dilemma it is important to look into the future of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka.

Although the President declared that hereafter there are no minorities in Sri Lanka, the Tamil people will continue to speak Tamil and maintain their unique cultures in Sri Lanka. As we consider this issue it should be taken into consideration that in this post modern era where different cultures and languages meet in the same market place people have been strengthening their identities to become meaningful entities in society. Sociologists are gradually realising that the Western expectation of the “Melting Pot” theory of the past century, where people are expected to integrate into the main culture, creating this “pot”, is not happening.

After this “humanitarian” war many Tamil people from the former LTTE controlled areas are now in the IDP (internally displaced people) camps. According to Government sources they now trust the Government and they have given up their allegiances to the LTTE regime. When we met these people we could notice the confusion in these people. For instance one elderly lady told us that she was not an LTTEer but two of her sons are “Mahaweerans” (literary meaning Great heroes). The Sri Lanka Tamil term Mahaweeran is very much similar to “Ranaviruwo” (literary war hero) in Sinhala. The term in Tamil, Mahaweeran, is pregnant with meaning and it gives strength and courage to Tamil people in the same way that the Ranaviruwo functions among many Sinhala people. As the realities of this nature among Tamil people are going to remain for a very long time there will be repercussions from this in time to come. At the moment it is too early to predict these repercussions as these people are in a desperate situation as IDPs.

The fact that LTTE was well established in many countries such as Canada and England is going to affect the future endeavours of Sri Lanka regarding Tamil people in particular. Although the militant group who were called terrorists because of their actions are defeated, the concerns that they presented to keep their power locally and globally are still lingering all over the world. The huge number of IDPs from so-called former LTTE controlled areas will contribute to keeping alive and strengthening these concerns in the global scene.

In all the celebrations, especially in the South of Sri Lanka, after the defeat of the LTTE, the impression is given that all the “minorities” have to live at the mercy of the majority. For instance a 10 year old girl asked me why is that people are using the Buddhist flag to celebrate victory over the LTTE. Then she said it may be to show that they are against Hindus because Hindus are generally Tamils. I strongly believe that we are called to learn a lesson from this innocent 10 year old girl who represents the future generation of our country.

In this post modern era if we are to have lasting peace we have to respect the self determination and the boundary maintenance of Tamil people in Sri Lanka. Everything possible should be done to fashion positive and constructive leadership to fill up the huge gap created by the downfall of the LTTE in Sri Lanka. To have positive results this should be done by the Tamil people for Tamil people. Others may act as facilitators without disturbing the natural course of acting in this regard.

10

Call for Moral Passover from Babel to Pentecost

Sri Lanka is a land blessed with people from various cultures, languages and religions who live in this Island, making it their motherland. History tells us that although at times they have had tensions, generally they been living together with a spirit of tolerance, respecting each other’s differences. This was apparent in Sri Lankan kingdoms before the 16th century, prior to Western colonisation. For instance, in medieval times the image of the bull was removed from the moonstones - Sandakada pahana - as it was a sacred animal in Hinduism. In this way people lived in diversity but in unity rather than unity in diversity.

Things began to change from the 16th century with colonising by the Portuguese, Dutch and British who came from homogeneous, ethno-religious identities dominated by one language. Portuguese spoke Portuguese and acknowledged the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, while the Dutch spoke Dutch and accepted the 'reformed' faith. The British, who were the first foreign power to conquer and occupy the whole island, spoke English and their established Christian religion was that of the Anglican Church. Drastic changes took place under British rule and the whole island was governed by a homogeneous ethos, giving prominence to the English language and Anglicanism. English gradually became the official language and the Anglican Church was the main Christian church of the colony of Ceylon.

When Sri Lanka gained independence from the British Empire in 1948, Sri Lankans did not have a clear model to replace this homogeneous form of English and Anglicanism. Each group was determine to promote its own language, religion and culture without having a clear vision of harmonious existence as one nation in their motherland. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, this has led to ethno-religious and cultural tensions, bringing chaos to this Paradise Island. How, then, should Christians live in harmony in this multi-religious, cultural and linguist context? What sort of inspiration can we derive from the the scriptures?

The story of the tower of Babel tells us how human beings who spoke one language wanted to build a tower to reach up to Heaven so as not to be scattered over the face of the earth. They became inward looking and sought to create a powerful a culture of their own based on one language. This is a valuable lesson for us today in Sri Lanka. As Sinhala, Tamil and Eurasians we have been trying to build our own towers of Babel to reach Heaven. We have became very self centred and selfish with our own languages and cultures. We have become confused, having to speak many languages. It is evident that our towers of Sinhala, Tamil and English are falling down, but we make desperate efforts to keep them standing and active. This is true both of the church and of the state. Often we Christians boast that we have people from all the three main language groups in Sri Lanka. Does this mean that we are free from contributing to the building and maintaining our own towers of Babel?

The story of Pentecost gives us the best model to adopt in this chaotic situation. The first Pentecost brought people from many cultures together, but not on the basis of one language or culture. What brought them together was the spirit of truth rather than their religious institutions. Though they spoke in their own languages they were able to understand each other.

How is it that today we can speak in our own languages yet understand each other? We see this among small children. I have seen this at the Theological College of Lanka Pilimatalawa. When children come together from Sinhala, Tamil and English backgrounds they speak their own languages yet understand one another. Then gradually they begin to speak each other’s languages. I remember a small Tamil boy challenging me when I spoke to him in my broken Tamil. He said: “Why are you speaking to me in Tamil? Speak to me in Sinhala because I understand Sinhala.” He said this in English!

We should remember that God has created diversity for us to celebrate, not to divide us.. In the sight of God all languages and cultures are equally valuable. Let us not be in such a hury to condemn sister faiths in our country. As Christians we are called to have the mind of Jesus. When the Samaritan women at the well asked Jesus the right place for worship He said it was not in the mountain nor in Jerusalem but we should worship God in spirit and in truth. He told his disciples that when the spirit of truth comes he would lead them into all truths. The most important thing is to obey the spirit of truth in all our endeavours and not condemn those who are not in our camp. Remember the response of Jesus when his disciples rebuked those who healed the sick in His name. Jesus said: “Those who are not against us are for us”

As human beings and Christians we should learn to live in symbiosis with other people of cultures, religions and languages. To do we must learn to think globally but act locally. Otherwise we may become global people who forget their roots or have the temptation to become too local and forget the global realities.

Therefore as mature human beings and Christians let us learn to be local in the context of our global world and to think globally without being isolated from local realities.

11

Sumanagiri Viharaya and Lanka Devadharma Shastralaya (The Sumanagiri Buddhist Temple and the Theological College of Lanka) – Three decades of “Xenophilia”

In December 2008 the Christmas programme with cultural elements organised by the Theological College of Lanka was held in an unconventional manner in the Sri Sumanagiri Viharaya. Devotees of the temple extended their cooperation by supporting the arrangements for the programme and by supplying short eats and sweet meats to entertain the brothers and sisters who came to the temple from the Theological College.

The saga did not end with Christmas: five months later in May 2009 a Wesak programme organised by the Sri Sumanagiri Viharaya was held at the Theological College of Lanka. The children of the temple’s Daham Pasala or Sunday school and the children of the Nandana Pre School of the Theological College of Lanka took part in the programme by singing Wesak Bhakthi Gee or Wesak Carols. This programme was facilitated by a Long Vacation Field Education Group of the Theological College of Lanka. At the end of the programme the community of the Theological College of Lanka extended their hospitality to the brothers and sisters of the village who shared responsibility in making this programme a visible reality.

These two noteworthy exceptional programmes were held not as isolated happenings but as a result of the long and affable relationship which has been growing steadily for over three decades.

It was in the 1980s that the then Principal of the Theological College of Lanka invited the Ven. Pallagama Dhammissara Thero to teach at the College. As this invitation was gladly accepted by the then Chief monk of Sri Sumanagiri Viharaya (which is commonly called the Kudugala Pansala), the relationship between these two institutions started by sending Ven. Pallagama Dhammissara Thero to teach Buddhist Philosophy and Sinhala literature to the theological students at the College.

This mental feeding through the teachings of the Ven. Pallagama Dhammissara Thero was strengthened by the mutual physical feeding through a natural process. Sometimes when the monk came for lectures the College made arrangements for him to have Dhana (midday meal) at the College while some students enjoyed the food offered by (members) Dhayakas of the Temple.

In the mid 80s, when the Ven Pallagama Dhammissara Thero was physically getting weak, he introduced his chief disciple, Ven. Buddumulle Sumanaratene Thero, to teach practical Sinhala to the Tamil students at the College, enhancing the continuation of this link by handing over the responsibility to the next generation. Gradually Ven. Sumanaratane Thero took over from his guru the responsibility of teaching both practical Sinhala and Buddhism at the College and he still teaches Buddhism to the students. From time to time he has also been functioning as a patron of the Sinhala association of the Theological College.

Now all over the island of Sri Lanka Sumararatne Thero has students who are Christian priests. This has created a lasting impact on society to facilitate Xenophilia especially among Christians and Buddhists in Sri Lanka.

This exemplary relationship between these two institutions was possible because of the renunciation of strong boundary maintenance of these two establishments for the mutual spiritual growth. Through this natural ongoing and growing relationship both parties are able to learn from each other, which in turn has enriched them socially and spiritually.

12

Significance and Derivation of Christmas

Why do people celebrate Christmas? A straightforward answer to this question is that Christmas is the birthday of Christ. Does this mean that Jesus was born on the 25th December? No, it does not mean that He was born on December 25th. The truth is that nobody knows the day on which Jesus was born. Then one may ask the reason for celebrating Christmas on the 25th December every year. This is a complex and complicated story, which needs to be investigated to have a sound understanding of Christmas.

It is clear that the early Christians did not celebrate the birthday of Christ. In the New Testament of the Bible, apart from the records of the birth of Christ we do not find any record of these early followers of Jesus Christ celebrating the birthday of their leader and master. This is not something surprising as Jesus was a Jew and most of the early followers of Jesus were Jewish people. For Jews birthdays were not very important as for the Romans or Greeks. In this background the only clear birthday recorded in the New Testament is the birthday celebration of King Herod, after which event John the Baptist, the forerunner of Jesus, was beheaded.

According to the generally accepted history of the Christian Church Christmas has been celebrated on 25th December since 354CE. Before this time, and after the New Testament period, this festival was celebrated on 6th January. It is necessary to understand the context of January 6th to comprehend the festival that was celebrated on this date. In pagan antiquity 6th January was the feast of Dionysus the Greek vegetarian god of wine. It was the belief of the followers of this god that by transforming water into wine this god revealed his divine power. Very probably, when the early Christians gradually initiated the celebration of the incarnation of God in Jesus the established legend of Dionysus would have created a significant ground to make the nativity of Jesus effective and meaningful. This is clear in the way in which they celebrated the Epiphany on the 6th January by commemorating the feast of the power of revelation of their God in a way by displacing the feast of the epiphany of Dionysus.

On the other hand the gradual development of 25th December as the nativity of Christ from the mid 4th century cannot be understood without a sound understanding of the mid winter festivals of the ancient world. These festivals were especially prominent in ancient Babylon and Egypt. At the same time Germanic fertility festivals were also held during this winter season. Along with the winter festivals the birth of the sun god was particularly associated with 25th December. For instance, the births of the ancient sun god Attis in Phrygia and the Persian sun god Mithras were celebrated on December 25th. The Roman festival of Saturn (Saturnalia), the god of peace and plenty, was from 17th to 24th December. These festivals were held with great festivity along with public gatherings, exchange of gifts and candles, etc.

Apart from these origins there are many other customs and traditions from other cultures which are embedded with Christmas. For instance the custom of decorating homes and altars with evergreen leaves of holly and mistletoe during the Christmas season came from the ancient Celtic culture of the British Isles where they revered all green plants as important symbols of fertility. The tradition of calling Christmas Yule tide in many countries is derived from an ancient ritual of burning Yule logs as part of a pagan ceremony associated with vegetation and fire. This community act was performed with the expectation of magical and spiritual powers. It is believed that the widely venerated Saint Francis of Assisi introduced the practice of making cribs by making a model of the scenes of nativity to re-enact the birth of Christ in order to bring spiritual revival to the laity. As is common knowledge, singing is part and parcel of almost all cultures of the world. In the background of this “cultural universal” singing of the carols for Christmas appeared in the Middle Ages and by the 14th century this custom became an integral part of the religious observances of the birth of Christ. Apart from these customs, rituals and ceremonies there are many other traditions such as the Christmas tree and the observance of saint days that are intertwined with the celebration of Christmas.

When Christmas began to be celebrated on the 25th December this festival became meaningful to people as it was able to enrich the birth of Christ by absorbing the meaningful festivals already celebrated in society. This is the core factor that has made Christmas so important for people all over the world. In this particular context it is clear that Christmas is not a mere birthday party for Jesus Christ. It is a festival of light and life. This is clear in the following Bible verses taken from the traditional Bible passage read for Christmas from St. John’s Gospel (St. John 1.1-14),

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it…..”

Christmas has the power to bring many cultures, traditions and symbols together to uplift humanity to divinity and bring down the divine to humanity. It is the responsibility of Christians and others concerned to make this festival meaningful by adsorbing all life affirming and light generating festivals and activities to this festival. We can see that already this has happened commercially. It is our responsibility to make this happen ethically, morally, culturally and spiritually.

The necessity for this responsibility springs up in the post war contexts of many countries as there are people who still exist in bleak life threatening situations. Here the message of Christmas in not to look into their caste, code, class, ethnicity or religion, but to accept and honour them by respecting them and making them understand that their liberation and redemption is tied up with the salvation of whole humanity.

Share this page

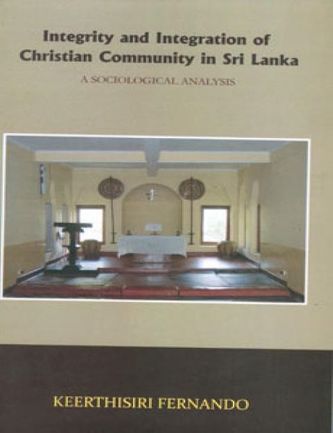

The Socio-Historical Context of the Christian community in Sri Lanka

v Christianity before the Portuguese

The island of Sri Lanka, located in the Indian Ocean, and situated at the southern tip of India, has been influenced by many cultures and religions of the world, at least from the era of the Indo, Chinese and Mesopotamian civilisations, the three great civilisations of the world. People, especially traders, travelled to Sri Lanka, due to its geographical location, which gave strategic importance to this country.[1] Archaeological evidence has been found which proves beyond doubt that this island nation was not isolated from the rest of the world in the course of human history.[2] This shows that many cultures and religions were moving across this island, influencing and reshaping the activities of the country.[3]

A book called Christian Topography (Ancient Greek: Χριστιανικὴ Τοπογραφία, Latin: Topographia Christiana) written in Greek in the 6th century by a person named Cosmos, records the existence of a Christian community in Sri Lanka. According to the author of this book, there was a Church with a Priest, a Deacon and the equipment necessary for the worship of Christians in Sri Lanka. In this work, first published in the original Greek by a Benedictine, and now translated into several languages, Cosmos says,

“ Even in Taprobane, an island in further India, where the Indian Sea is, there is a Church of Christians with clergy and a body of believers,” [4]

This Taprobane is undoubtedly Ceylon, for Cosmos says,

“It is called Seilediba by the Indians, but by the Greeks Taprobane”. [5]

Referring to this Christian Church, he says again in the Eleventh book, in which he describes Ceylon:

“ The island has also a Church of Persian Christians, who have settled there, and a Presbyter who is appointed from Persia, and a Deacon and a complete ecclesiastical ritual. But the natives and their kings are heathen.” [6]

There are two archaeological finds in Sri Lanka that may be considered parallel to the above account of the existence of Christians in the country. The first evidence, coming from Anuradhapura, is a Persian cross belonging to the Nestorian Church; archaeologists unearthed this in 1912.[7] A Baptismal font found in Mannar, and presently kept in the Vaunia museum, is the second evidence, and is also an artefact likely to belong to the Persian Nestorian Church. The popular belief is that even if there were Christians they were foreigners who did not have much to do with the affairs of Sri Lanka. But this popular belief is challenged with the discovery of the Mannar baptismal font, which was most probably used to baptise Christians in Sri Lanka.[8]

According to Chulavamsa, the supplement to the Sinhala great chronicle Mahawamsa, a minister called Migara built a temple and dedicated it to a person called Abisheka Jena. In the Pali language Jena means a person who has conquered himself, and Abisheka is the anointed or the enthroned one. The quotation from the Culavamsa is given below:

“The Senapati by name Migara, built a parivena called after himself and a house for the victor Abiseka. He sought (permission to hold) a consecration festival for it even greater than that of the stone image of the Buddha.” [9]

Professor Senarath Paranavithna, the first Sri Lankan Archaeological Commissioner, says that this Temple was dedicated to Christ, which means the anointed or enthroned one in Greek. In the scholarly account of the story of Sigiriya by Professor Senarath Paranavithna, the author shows that this minister, Migara, from South India, was a Christian who laboured to spread Christianity in Sri Lanka.[10] Migara had served in the courts of both the kings Kashshepa and Mugalan in the 5th and 6th centuries AD. Along with these records, among the archaeological discoveries there were Greek, Roman and other Near Eastern objects of Christian influence from the 1st century, found in Sri Lanka. From the 6th century to the beginning of the 16th century there are isolated records that could be connected with the existence of Christians in Sri Lanka.[11] Hence it is clear that Sri Lanka was not isolated from the influence of Christianity before the arrival of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka. Yet unlike India, when the Portuguese arrived here there was no clear evidence of the existence of Christian communities in Sri Lanka.

The introduction of Christianity and its impact in the context of Western Colonialism -The arrival of the Portuguese

v Divided and devastated Kingdoms of Sri Lanka

When the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka at the beginning of the 16th century it was a time of great political instability in this country. During this period Sri Lanka was divided into three kingdoms, namely Kotte, Kandy and Jaffna.[12] However, the goodwill between the kingdoms was not healthy for the integrity of Sri Lanka. Not only between the kingdoms, but also within the kingdoms, there were power struggles which brought the Sri Lankan context into a very much weaker position politically and economically. At the beginning the Portuguese did not have any intention of getting involved in the affairs of the divided and devastated kingdoms of this land. Their two main intentions involved their interest in spices and the spread of Christianity. To win new lands for Christ was a responsibility given by the Pope in the context of the Christian reformation in the west. The official statement issued by the Pope, outlining this responsibility through the Vatican, was called Padroado. Regarding the Padroado and the King of Portugal, F.Houtart has observed,

“Just as the Papacy had granted to the Portuguese sovereigns the right of conquest, so also it granted to them the right to supervise the ecclesiastical organisation. The king, a political actor, the organiser of the commercial enterprise, and consequently an economic actor, became by this fact a religious actor too” [13]

v The kingdom of Kotte.

The Kotte kingdom became the most important and powerful kingdom of Sri Lanka during the reign of King Parakrama Bahu VI (1414-1467A.D.). This was a period of revival and of great cultural activity, where agriculture, religion and literature flourished. King Parakrama Bahu VI was called “chakravarti” or the Emperor of Sri Lanka, and other sub-kings or rulers of the other areas paid tribute to this great King and honoured him. After him six kings ruled Sri Lanka from 1468 to 1521. However, none of them were powerful enough to exert power over the other kings and rulers of this country. This was mainly due to the conflicts and crises of the royal families.

After the above historical era one of the main tragedies in the history of Sri Lanka took place during the reign of King Vijaya Bahu (1509-1521). This was the murder of King Vijaya Bahu, and it led to the division of his kingdom into three parts, each ruled by his three sons. Buvaneka Bahu became the King of Kotte, Mayadunne the King of Sitawaka, and Raigambandara, the King of Raigama. Mayadunne was a man who, wanting to expand his kingdom, with one stroke of his sword annexed Raigama and established his power and authority. This made Buvaneka Bahu, a weak ruler, afraid, and so he invited the Portuguese to protect him from his brother Mayadunne.[14] During this era, since the Portuguese dominated the affairs of the Indian Ocean by diminishing the authority of Muslims, they welcomed this invitation gladly. This paved the way for the Portuguese to enter into the internal politics of our country. Ultimately this invitation of Buvaneka Bahu, instigated for a political purpose, became a landmark in the history of the Christian Church in Sri Lanka.[15]

v The Portuguese and Christianity in midst of political instability in Sri Lanka

When the Portuguese began to understand the great political instability of Sri Lanka, they gradually penetrated the political arena of the country by using this instability as their main weapon. In the midst of this political instability, Portuguese missionaries wisely kept their distance from the power struggle within Sri Lanka. Even though the missionaries maintained this distance, they were supported and protected by the Portuguese colonial power. Portuguese missionaries and their mission were very clearly a part and parcel of the Portuguese colonial expansionism. [16]

v The impact of Conversion to Christianity

Conversion of the members of the royal family and elite

Though King Buwanakabahu of Kotte enlisted the assistance of the Portuguese he did not become a Christian. This may be due to the fact that he did not want to displease the ordinary Buddhist people of Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, he invited Christian missionaries to come to Sri Lanka. As a response to this invitation five Franciscan missionaries came to Sri Lanka and began their work in the kingdom of Kotte. These missionaries were entrusted the task of educating the young prince Dharmapala who was the heir to the throne of the kingdom of Kotte. The King of Portugal enthroned this prince according to the invitation by the King Buwanakabahu. Regarding this enthronement, P.H.D.H.de Silva has observed,

“The embassy despatched by King Bhuvaneka Bahu VII of Kotte entrusting the custody and protection of his grandson Prince Don Juan Dharmapala to the King of Portugal reached Lisbon in August 1541. The envoy carried a royal sannasa or ola requesting that King John III of Portugal be pleased to acknowledge and proclaim Prince Dharmapala as the rightful and lawful heir to the Sinhala Throne after the demise of King Bhuvaneka Bahu. The King of Kotte also sent an effigy of the Prince which was deposited in an ivory casket, the panel of which were carved with historical scenes relevant to the Kingdom of Kotte.”[17]

Therefore the prince Dharmapala had a Christian upbringing right from the beginning of his childhood. This created a new page in the history of the royal dynasty in Sri Lanka. Here we see how a tension between two brothers, Mayadunne and Buwanakabahu, brought into existence a Christian royal court, which became a decisive factor in the future history of Sri Lanka.